Hi friends, I am trying something different with this edition. I’m working on a collection of short stories from my time in Kenya, and wanted to give you all a taster. Stories that show a few hard earned life lessons that have shaped my worldview and work. Please let me know in the comments and “hearts” if you like this type of writing. — Melissa

I met Evans early into my Kenya years. Running down a busy, dusty road in heels and a skirt, I was late and none of the matatus were stopping. Matatus in Kenya are the public buses that few expats take but I was new and money was tight.

Visiting tourists love matatus for their colourful, wacky decorations, and hate them for constantly swerving in front of them as they manoeuvre around their routes as quickly as possible. For us passengers, matatu rides were crowded and sweaty. We paid around 30 cents a ride and the rule was there was always room for one more.

Not catching a matatu meant the next cheapest and fastest option was a boda boda, or a motorcycle taxi.

“Can you get me there haraka?” I asked a rider sitting on his bike on the side of the road. I hadn’t dared to spend much time on these bikes, who split lanes and hopped up on sidewalks.

I climbed onto Evans’ bike and I felt safe with him. He stayed with me that day and then that week as I whizzed between checking on the operations of our early clinic in the Mukuru slum, pitching potential investors in the cool gardens and rooftop restaurants of Kilimai, and negotiating with suppliers down in Eastleigh and the Industrial Area.

Over the next year I saw Evans multiple times a day almost every day of the week. He knew which bars I liked and what I was like when I was upset. He got to know my coworkers, and he brought our foreign interns with their backpacks, boxes of medicine stacked high, nurses with immunizations in cool boxes, and marketing materials to our growing network of clinics. We talked and joked around and I really trusted him. Once I had to leave my macbook air with him when entering the high security American Embassy to renew a passport. Another time I had to leave my phone with him as I visited a friend’s cousin who was locked up in a crowded Kenyan male prison for petty theft. Nervous, without a phone, and still in my red dress skirt and black top, I walked with the prison guards towards the cells packed full of mostly teenagers while Evans waited for me outside. He would carry my house keys to friends.

I grew close to Evans at a time when it felt good to have someone I could trust.

Life in Nairobi in 2012 moved fast. I moved there from New York City to build a social enterprise providing low-cost, tech enabled healthcare in the slums. I made friends quickly and my life was full of sunny outdoor concerts, events with emerging fashion designers and artists, and salsa nights at the Brew Bistro.

They were also full of adversity.

I also had to negotiate with village elders demanding payments to operate in their territory. I lost people in terrorist attacks. My first apartment was robbed a few months after my first clinic was robbed. After the clinic robbery, our staff were mocked by their peers for not standing up to the thieves. It was both an exhilarating and daunting time. Things changed in an instant, and from my wifi to my startup team members cycling in and out to other positions, there wasn’t a lot that was constant, predictable in my life. And this uncertainty chipped at the foundations of my ability to know, to relax, and to trust.

So without ever making a conscious decision, it felt good to trust Evans fully.

Two years later, I moved apartments. I found a sunny garden studio and was living alone for the first time. As I unpacked and set up the internet, I realised I needed to find a maid. I know this makes me sound like a rich housewife. Having maids in my previous Nairobi apartment shares initially made me uncomfortable. My friends and coworkers all had maids, some had drivers, nannies and gardeners and even though it was common, hiring someone almost always happened through personal networks. So I thought I might as well give work to someone who needs it, and I asked Evans if he knew anyone looking for a job.

Soon a woman sent by Evans was in my house, mopping away the infamous red dust of our dry city. Unpacking in the other room, I felt a weird feeling deep in my gut. But you can’t take away someone’s livelihood because of a bad feeling.

That weekend, friends threw brought used furniture, bottles of wine, and mugs and we stayed up late warming the house. I got to know the women cooking chapatis and selling avocados on the corner outside our gated compound. Within two weeks, my hands were feeling around the desk drawer for some money from my emergency stash, but nothing was there.

I knew what had happened without wanting to admit what happened. I told Evans immediately, and I can’t remember the order that these next events played out.

“It was her,” he said angrily over the phone. Biking over to my house, he dumped a crumpled wad of bills in my hands. “I was searching for your money while she was out of the house, but the neighbours saw and chased me away,” he told me as he handed me a newspaper.

In the pile was few rupees, Singaporean dollars, Tanzanian coins. Had she gone through every drawer, every souvenir box in the apartment?

102:1 was scrawled in pencil at the top of the newspaper. I recognized the current USD : Kenyan Shilling exchange rate. Why did he find all of this, but none of the dollars?

At some point, this woman started to text me and tell me that Evans was the one who robbed me. He forced himself into the apartment while she was minding her own business, she wrote. “Don’t trust him. He talks about killing you.”

At another point, definitely after the crumpled bills and newspaper, Evans showed up at our clinic bleeding around his eyes. He was beaten, and needed stitches along the top of each cheek. He did not want to talk about the people who did it. This woman is evil, I thought. There is no way Evans would let himself get hurt for his share of a few hundred dollars. Right?

The cops got involved eventually. The woman had agreed to come back to my house! Evans shows up just after her, with four police officers. My small, new garden studio now holds a woman, Evans, four police officers and their four AK-74s.

“Where did you keep the money?” One of the officers asked.

I handed them a box.

“It is empty!” he exclaimed. The guns move every time they shift their weight.

The woman is talking and I don’t remember a word she says until she calls Evans her lover.

“It’s true. She is my mistress.” He says.

The four police officers and the four AK-74s are silent.

Eventually, one of the officers suggests they take the woman and Evans down the station for further questioning.

“You’ll need to drive us,” an officer tells me. There are many more police officers in Kenya than police cars.

The seven of us pack into my five-seater car and I drive them to the station. It’s less than an hour before I get a call. “They both say the other is guilty,” the officer tells me. He suggests I try and get the money back from both of them.

I ask if they are going to visit her house. But a real search or investigation was never in the cards. I can’t help but wonder if a deal was made between the six of them in that station.

They are released, and Evans tries to pay me back some of the missing money, which makes me think I should trust him again. He’d never talk to me again if he were a part of it? The woman continues to send menacing texts for a few more weeks warning me about Evans, which make me despise her more but on some level, they seed doubt.

“She bought a T.V.” Evans tells me one day. They are still neighbours.

He takes me to work for a couple more months, giving me discounts and noting down the slow contributions those discounts make towards what went missing. He tells his wife everything and then starts drinking more. His neighbourhood is full of cheap beer and homebrew liquor. One day, when turning out of my street, the whole bike topples over with us on top of it.

“Are you drunk?” I ask him as I get up from the pavement, brushing off gravel, shaken but unhurt.

I call him for rides less. I start to take taxis. I offer him money for AA. It becomes too painful to keep seeing him. To have that constant reminder of those earlier days when I trusted him to fly through the streets of the city with me, looking down responding to emails, on the back of that bike. “I do believe you,” I tell him, and I mean it. But I keep him at a distance for the remainder of my years in Nairobi.

I look back on this time with mixed emotions. This is a story about the complexity of separating micro-decisions from macro systems. About learning to continuously trust, despite the vigilance that can build up over the course of a life.

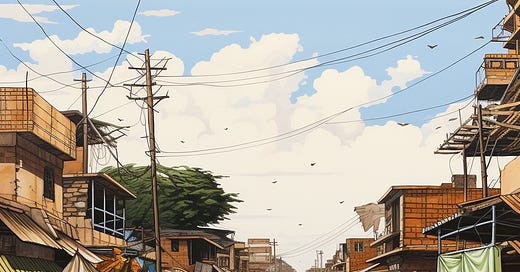

I didn’t know this woman for more than a few weeks, but I had an understanding of her life. Her home is in Kawangware, with >100k neighbours living mostly in single story slapdash iron structures cramped between the surrounding formal settlements. It is hot and crowded, and everyone is trying to make it out.

People there earn a few dollars a day, and if they’re lucky, they earn it predictably. The money she stole from me was over ⅔ the average annual salary in that community. Without formal work, government benefits, running water or public infrastructure, the system is pretty rigged against the residents of Kawangware. Most people think getting out means winning the lottery or cheating the system.

Our environments shape us.

The good news is, as we accept this, we can think differently about people who do “bad things.”

I’m not excusing the robbery, but a stroll around the neighbourhood can sure as hell explain it. And I know it will be an uphill battle for Evans to escape the drink and for his friends to escape dishonest decisions until they have the chance to escape that environment. It is hard to judge individual actions without judging the institutions that created these pockets of densely concentrated poverty.

As Buckminster Fuller said, it is easier to reform the environment than it is to reform people. And this vision of a reformed environment – one that makes living easier – is the thing that continues to motivate my work today.

A big thanks to

, , Rik , , , and Eric for the patient edits over the course of this piece.If you liked this, please let me know in the comments ❤️.

A brilliant unfolding, I was gripped in the unfolding and loved your closing commentary.

Wowowow - I just took a much needed break from life in texas. Thanks for the immersion I experienced in this essay.