As you, my readers, know, there’s a lot we need to improve when it comes to funding early stage, high-impact startups.

Today I’m questioning fund focus. “We do maternal health, we do financial services.” Every funder has a focus. And I get why (more on that later) - but I think our devotion to our chosen cause creates some perverse outcomes.

Here are a few thoughts on funding the vital neighborhood.

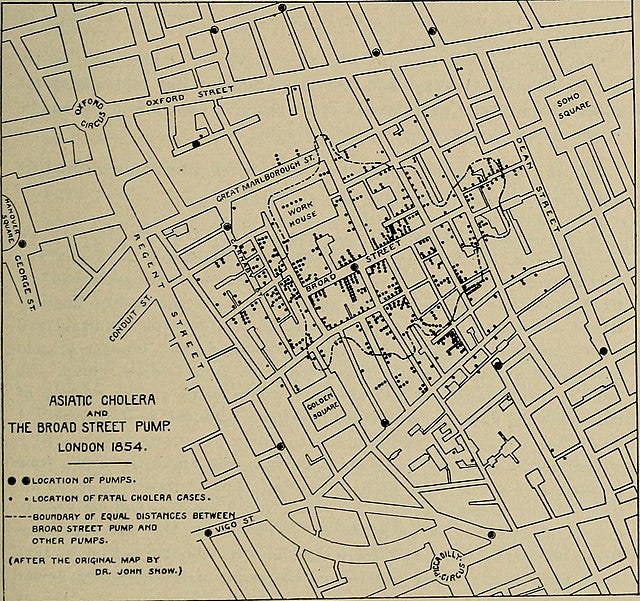

In the midst of the 1800s, cholera was wreaking havoc upon the vibrant streets of London, preparing to spread across the European continent. Picture Soho, not as the bustling hub of cocktail bars and theaters we know today, but as an overpopulated slum, the epicenter of this epidemic. In the face of impending doom, three-quarters of the neighborhood’s residents fled London. The prevailing belief was that cholera, like many other diseases, stemmed from “miasma”, the dreaded bad air.

How did we come back from this state of disease and desertion? Enter: Physician John Snow.

Snow traced cholera cases back to one source. He mapped fatal cholera cases and noticed they all seemed to spiral out from one location. The Broad Street water pump.

He presented and pleaded his case, but it wasn’t easy to change how people thought about disease. After much persuasion by Snow, the local council agreed to remove the handle from the water pump in Soho, stopping the flow of contaminated water. And lo and behold, cases immediately began to subside.

With this discovery, the seeds of modern epidemiology were sown. We could now devise targeted disease prevention strategies by comprehending the underlying determinants of health within a given environment.

However, nearly two centuries later, coaxing healthcare investors to care about the metaphorical water pump is an uphill battle.

I’ve seen it as an urban health founder, and as a healthcare investor. It’s painfully obvious to me that we need to put our environments back at the heart of the healthcare conversation. Yet we encounter a mighty opponent: the rigid industry and sector definitions adhered to by many funders.

Let’s take a little journey through the challenges of funding pattern-breaking entrepreneurs, the quest for healthier cities, and yes, modern cholera outbreaks.

#1: It’s hard for mold-breaking entrepreneurs to access capital

Luckily, now we know to test water when looking for the source of a cholera outbreak. This is easy with the right people and laboratory equipment. Unfortunately, these ingredients can be a tall order in the areas where cholera still rages today.

That’s why I was excited to get to know the founder at OmniVis, a startup that has developed a 30-minute diagnostic for cholera in water. It is a lightweight, portable device that can be taken “in the field” where the luxury of labs are a distant dream. It’s an incredible public health breakthrough. But here’s the rub. OmniVis doesn't exactly fit the mold of a typical medical device company. It’s made to diagnose environments, not people. But it looks like health to water investors. So the innovation struggled to find a funding home.

The team pivoted away from cholera, rapidly adapting their technology to detect pathogens like e.coli in food and are making great progress in their new space. Foodtech funders started to bite.

I’m proud of them because food supply chains are still an important part of building a vital neighborhood. Yet, I can’t help but feel a pang of sadness when thinking of Somalia, where more than 11,000 suspected cholera cases have been reported this year. The urgency is real, and it's high time we bridge the gap between breakthrough technologies and much-needed funding.

#2: Strict verticals miss the opportunity for flywheels

My friend Sonak developed an incredible program for diabetes and hypertension that linked treatment to savings and investment groups. People were more likely to get care, and more able to invest in their health with a foundation of financial access. He’s written extensively about this (so have I) – the point is, health outcomes, the kind that are needed to save lives, drastically improved.

But it’s not quite microfinance, and it’s not quite healthcare, so it’s also struggling to get the capital it deserves to scale. A key issue here is that one sector (let’s say, healthcare) is unwilling to take on the risks inherent in another sector (here, finance).

What if something goes wrong?

What if we lose healthcare donor money on a savings and loan program?

Linking the programs created a clear flywheel for better financial and healthcare outcomes for people. But it also created an uphill battle for funding.

Just like the example with testing water, we’re missing out on some very intuitive solutions here. Like healthcare solutions that integrate with the things we want. Like money! (A finger prick isn’t too high on anyone’s wish list).

Towards Systems, not Silos

Let’s take a little empathy intermission. I get verticals! I think it makes sense as a funder with limited resources to focus on an area they care deeply about, and have deep knowledge of. It helps with expertise, evaluation, and keeps investment teams lean and efficient.

But if an impact investor really wants to move the needle on disease eradication, a fund thesis centered around “how might we halve diabetes cases in Africa” is going to lead you to backing very different things than one centered on healthcare.

In my work modeling how to fund healthier cities, here’s what this looks like:

An intersectional thesis. Building a place that enables good health requires clean air and water, safe streets, healthy food systems, safe, affordable housing, community and mobility. In contrast, the United Nations’ work on Healthy Cities is pretty focused on the unique health needs of urban residents, and the gaps in treating them.

An innovator map. It’s not just what we want to fund, but what businesses they wish existed (to create flywheels with). This enables collaboration with other types of funders to help build missing puzzle pieces.

Comfort with soft and qualitative data. It is a lot harder to get hard data on your role in systemic change. But we’re collecting data on who our healthy city innovators are serving, what those customers are saying, how they are growing, and building a database of insights that could fuel some really interesting evaluation down the road.

I need some feedback from you all on this one. Last month, I railed against a lack of focus in donor communities, a broad quest for innovation that results in a well-intentioned judge comparing a goat rearing program in Pakistan to a digital diabetes intervention in South Africa. Lack of focus is a problem because:

It diminishes the role of expertise in evaluating solutions

It results in a much less supportive funder, without experience and networks to help

It creates lengthy and weird funding applications meant to prove an idea is the BEST THING in the WORLD.

And now this month, I’m railing on silos, which are essentially a form of focus.

Please leave a comment and let me know what you think about the tradeoffs in focused vs. systemic thinking when it comes to funding game changing ideas. Ultimately, I believe we can build a future where healthy cities flourish, and diseases like cholera are but distant memories. Let’s take some risks and try new things!

Until next time,

Melissa

If you liked this, you’ll like my friend Erin’s twitter account. Thanks Erin for the edits!

I'd argue it's an error of our age to imagine that "focus" that isn't backed by "systemic" thinking works. My friend who studies physics by firing particles at each other would seem like a prime candidate for "focus" but it turns out that even there, to actually do the work he needs to know about a lot more than just the physics of particles - because even a particle accelerator is a *system* composed of many parts, all of which need some attention at various moments.

My hamfisted two cents would be: Focus might be for aims/goals - systems are for how you achieve them.

I totally agree, though on the flipside, a challenge I've faced (in my case, advocating for interventions in things like urban health, transport and housing as part of a strategy for economic growth - clearly these things are related and in many cases even fundamental, but not on the face of it classic "economic development" interventions) can result in a sort of collapse where everything becomes about everything. Because everything is connected, it becomes increasingly hard to define clear domains or delineations. Some respond by simply launching in and solving other problems; others say, well, if someone else has responsibility for urban health, just leave that to them. My approach so far has been to try to join things up as much as you can, signpost rather than replicate, and fill any obvious gaps when required. It still feels quite uncomfortable often and I don't think there's a straightforward answer but I'd be interested in your view...

Anyway I love the John Snow so always interested in a pint :D